This an attempt of mine to share my frugal knowledge on Chinese and Japanese characters. I'm tackling the two, instead of say just Japanese, because for one thing, both languages are linked to each other (or rather it's more proper to say that Japanese is linked to Chinese). Moreover, while there are several books and online webpages there that tackle Chinese and Japanese exclusively, I think it would be more interesting on my part to tackle them both and how they're related to each other.

In the previous lesson, we established that Chinese and kanji characters are more like symbols rather than the phonetics common to Western languages. So how does one go about figuring how to pronounce a word?

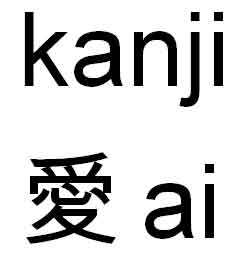

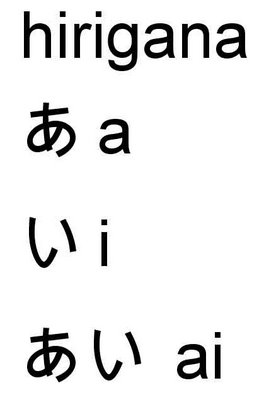

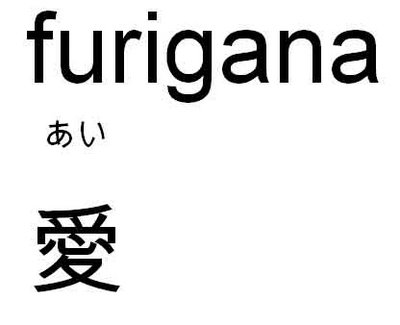

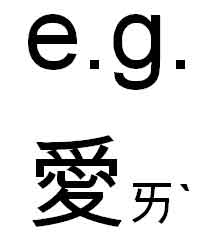

Let’s take the kanji character for love, “ai”. In Japanese, there’s two ways to write this: in hirigana, and in kanji. Obviously, hirigana will reveal how the kanji character is pronounced. In this case, the kanji character is used more often than not, and resorting to writing ai in hirigana betrayers a person’s lack of familiarity with the language. As a learning tool, certain kanji characters are sometimes accompanied with hirigana characters written above them (and more rarely, katakana characters if the author intends to have the kanji characters pronounced in a different or foreign way). This is called hirigana and can usually be seen in books and comics designed for teenagers (or basically any printed material that’s helping the reader make the transition from hirigana to kanji).

The question you might be asking is why bother with kanji at all if there’s always a hirigana equivalent for it. Well for one thing, as mentioned in the previous lesson, kanji characters speed up the reading process. The other, perhaps more important reason, is that it helps differentiate from other similar-sounding words. In English, it’s what we would call homonyms. There’s only so many letters in the Japanese alphabet and it is inevitable that certain words will be pronounced the same as other words. However, a distinct difference will be how they are written. It could be a different combination of hirigana and kanji characters or simply a different kanji character altogether. Third is the fact that kanji characters are like symbols, and kanji characters are composed of other kanji characters (I call them “root words”). Sometimes, the meaning of root words are related to the kanji character which they’re a part of. For example, in the case of ai, it contains the kanji character for heart, shin. It’s not a significant logical leap to associate heart with love.

Chinese, on the other hand, poses a different problem. Unlike Japanese which has three scripts (hirigana, katakana, and kanji), it simply has one. Its entire alphabet are composed of kanji characters. So how does a Chinese person figure out how to pronounce a word?

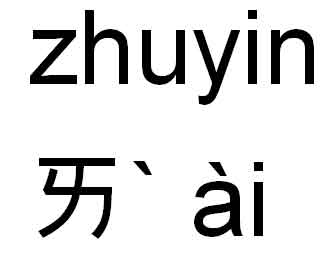

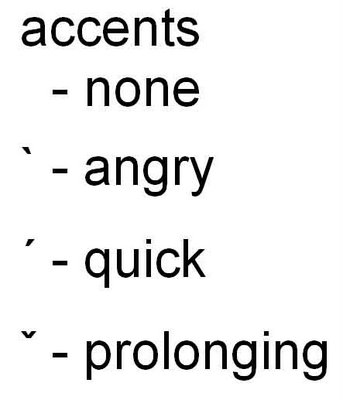

Well, there’s zhuyin, which is a pronunciation guide for the Chinese. If the Japanese have furigana which uses hirigana to guide readers on how to pronounce a kanji character, zhuyin is the equivalent of hirigana. However, unlike hirigana, zhuyin is never used as a standalone word but simply exists to show how Chinese characters are pronounced. You can think of them as the funky pronunciation guides preceding the definition of a word in English dictionaries. You only see them when you’re interested in figuring out how a word is pronounced but aside from that, never see it used in formal texts. For each Chinese character, a zhuyin will usually comprise of one or two characters, plus an accent note. Unlike Japanese, Chinese is monosyllabic: that is, there’s only one syllable sound for each character, whereas Japanese characters range anywhere between one to three. To compensate for this lack of variety, Chinese has four accents which act to differentiate similar-sounding words. Nonetheless, Chinese still has homonyms, and either the written characters or familiarity with the usage (in the case of actual conversations) enables people to distinguish between similar sounding words.

Of course if you’re an English speaker, you’ll probably be more familiar with romaji and pinyin. The former is used for Japanese, and is a guide on how to pronounce Japanese words using Roman characters. The latter is like romaji, except it’s used for Chinese characters.

No comments:

Post a Comment