This an attempt of mine to share my frugal knowledge on Chinese and Japanese characters. I'm tackling the two, instead of say just Japanese, because for one thing, both languages are linked to each other (or rather it's more proper to say that Japanese is linked to Chinese). Moreover, while there are several books and online webpages there that tackle Chinese and Japanese exclusively, I think it would be more interesting on my part to tackle them both and how they're related to each other.

Based on the previous lessons, one might think that just because you know Chinese you’ll automatically know Japanese (at least the kanji part) and vice versa. Unfortunately, this isn’t true. Will it be easier for you? In a way, yes, especially considering navigating through a Chinese and Japanese dictionary is the same, but I’ll get to that in the future. In the meantime, here are some significant differences.

First is the fact that both Chinese and Japanese might have the same kanji, but they’re pronounced differently. For example, in Chinese, water is pronounced as shui. In Japanese, however, it’s pronounced as mizu. However, that’s just the beginning. In Chinese, you can combine two characters to form a word with a new meaning. I call these compound words, and it’s much like English compound words. In Chinese, when you combine water with the character for location, wei, you get water level. In Japanese, the same characters can be combined to form the same meaning. However, the pronunciation becomes different in Japanese. Alone, water is pronounced as mizu, while the character that’s location in Chinese is pronounced as kurai (its meaning is also slightly different, meaning position or rank instead of a location). Combined, it merely becomes suii. It is important to note that in compound words, Chinese characters are always pronounced the same way, although their meanings can change. Japanese, on the other hand, alters in pronunciation depending on which characters it’s paired up with, as well as its meaning.

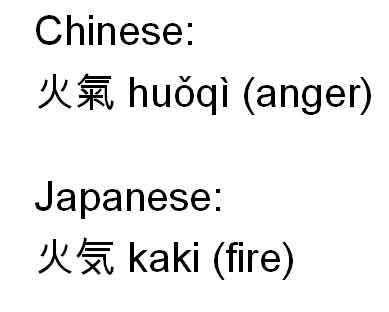

Of course sometimes, when you combine the same two characters, their meanings change. For example, huoki in Chinese means anger. Using the same characters for Japanese, you end up with kaki which stands for fire.

There are also situations when the Japanese kanji is supplemented by hiragana characters. For example, the character for new in Chinese is xin. In Japanese, it is atarashii, and it is comprised of a combination of kanji and hiragana.

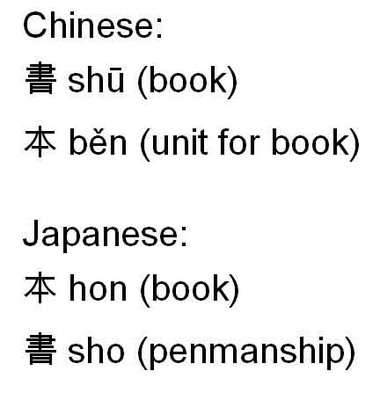

Then there’s the rare instance when the characters have been corrupted. For example, the Chinese character for book is shu. In Japanese, it’s hon. Yet these are two entirely different kanji characters. Where did the latter get its meaning? Well, hon has a Chinese equivalent. It’s pronounced as ben. It’s normally used as a unit for books. What I mean by unit is that in Chinese, in between a number and a noun is a Chinese character that’s used as a unit. In English, the closest I can think of is storm in a storm of crows or fleet in a fleet of ships. Now ben is usually a unit used to measure printed material, such as books. In Japanese, there are no such things as units. Shu still exists in Japanese, except its meaning is now penmanship rather than book.

Lastly, there are more Chinese characters than Japanese kanji characters. The Japanese government has 1,945 recommended characters to be used as a guideline by the populace but that number is still dwarfed by the number of total Chinese characters. To make a long story short, there will be Chinese characters that do not exist in the Japanese language. It is harder for a Japanese person to learn Chinese compared to a Chinese person to learn Japanese (because the former supposedly has a better mastery of kanji) but the Chinese person will still need to readjust to the different meanings of words he is familiar with, not to mention grammar and syntax. A Japanese learning Chinese, on the other hand, has a lot of kanji to familiarize himself with, in addition to readjusting to the kanji he already knows.

No comments:

Post a Comment